This episode is dedicated to two fantastic fans who had incredible questions, both about one of my favorite game mechanics: Betrayal! Here is a rundown on Inevitable Betrayal and the problems of Reputation.

Games with Risk Part II: Clank!

How crazy that after making an episode all about risk, I had the opportunity to play Clank! by Renegade Games. This self-styled “deck-building adventure” gives you the opportunity to compete with your fellow rogues to see who can gain the most and best treasure before the dragon returns to send you scurrying from his hoard with fangs and fire.

How crazy that after making an episode all about risk, I had the opportunity to play Clank! by Renegade Games. This self-styled “deck-building adventure” gives you the opportunity to compete with your fellow rogues to see who can gain the most and best treasure before the dragon returns to send you scurrying from his hoard with fangs and fire.

As players enter the castle, they take their first steps on a web of pathways leading through the castle and into the dragon’s deeps. In the deeps are a series of different artifacts, each worth a different number of victory points. Players must grab one of these and then race back towards the entrance before the dragon kills everyone.

Seems simple enough, but in order to win this game, players need to balance how deep they go in the castle, how valuable of an artifact they grab, and how quickly they can get back to the start. The game is complex enough that this balance is tricky to master! Plus, the deck you build defines how well you escape! So, things get really frustrating when the cards you need to move don’t show up.

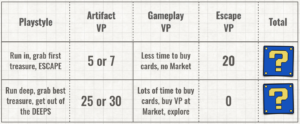

Meanwhile, the dragon ramps up throughout the game every time a player grabs an artifact. More damage comes out the more artifacts are stolen. Which means a perfectly valid strategy is to grab the cheapest artifact you can and then run for it before damage becomes overwhelming. Since other players will need to go deeper, they’ll be forced to spend more turns potentially taking damage. In order to score any points at all, players have to at least escape out of the deep and into the castle proper, where their can be safely recovered if a dragon burns their thief to a crisp.

Is this the best strategy? Well, simply delving deep and grabbing a better artifact can’t make up for failing to escape the castle. However, spending more time in the dungeon can grant you gold coins to spend at the traditional underground market! Whether you buy a key, a crown, or a backpack, you will gain new options and very likely more victory points. There are also plenty of victory points waiting to be found by players who are willing to thoroughly explore the Deeps. Finally, once you escape, you can’t improve your deck anymore, which means you stop gaining victory points by purchasing special cards.

This game quickly becomes a Stag Hunt problem for a group of friends, when one player decides whether or not to try the Escape strategy while everyone else is engrossed in heading into the Deeps. While it is absolutely a great strategy to win the game, you may hear some groans from your friends when you try it out.

This game quickly becomes a Stag Hunt problem for a group of friends, when one player decides whether or not to try the Escape strategy while everyone else is engrossed in heading into the Deeps. While it is absolutely a great strategy to win the game, you may hear some groans from your friends when you try it out.

Clank! is a fantastic game with a novel approach to the deckbuilding genre. The race for artifacts is tons of fun, and the dragon mechanic builds the kind of tension that makes you hold your breath. I’ll be picking up my own copy as soon as humanly possibly.

Designing a Puzzling Experience for the Overlook Film Festival

Confession time. I cried during E.T. Not because of the sadness of that poor lost alien flying back home but because that movie is terrifying. The scene where they set up the huge white tents and get set for dissection? Tiny little me just couldn’t take it. I’m no good at scary things! I close my eyes in the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland, for crying out loud. So I was the obvious choice to help design a game for Oregon’s latest festival of terror.

The Overlook Film Festival is a convention dedicated to the complete experience of horror. And so, OFF was held at the perfect venue: Timberline Lodge, famous as the setting for The Shining. Not content to simply let attendees sit around and watch movies, OFF brings in immersive projects that showcase the thrill of personal terror. So of course, there was timid little me helping develop the Immersive Horror Game.

Together with Dylan Reiff and the incredible team from Bottleneck Immersive, I helped design a four-day mystery experience, tracking the rise of a serial killer during the Festival using a clever set of puzzles and immersive moments. With some help from a bitter detective, a cheerful historian, and members of a secret society, we sent players across Timberline Lodge and Government Camp, searching for our devious little puzzles and special interactive moments.

Take this odd-looking cipher. Each of the main players received one fragment of a three-part piece of paper, carefully left in their hotel room. We used this mechanic as an icebreaker, so solvers would find each other during the festival. Once they put it together, they saw two major encrypted phrases. Along the top, a mixture of Morse code and the Freemason’s Cipher, which sent them to find a specific page in a specific book. But the second was entirely unclear. Was it five words? Was it five phrases with no breaks? This resisted simple decryption techniques, and players were stuck until more information came their way.

Well, the page in the book led to a phone number, which led to a person who recalls some strange code language, which eventually led to a fax machine at the Lodge with the decryption alphabet. Based on the Mary Queen of Scots cipher, this has extra characters for spaces and symbols representing “doubling the next character.” This second code had been intentionally time-locked, and gave additional story for players during the event.

Like escape rooms, games like OFF have a very different design goal than events like Puzzled Pint or DASH. Puzzles have to be shorter and created without a focus on master puzzlers. Puzzles should also be immersive, with solutions that could be easily found in the environment without having to use the internet or simply crunch data. Plus, the puzzle needed to be more about the experience than just finding the solution. Everything within the OFF Horror game was carefully crafted to lead to new ideas and new information, eventually allowing players the agency to talk to major characters become part of the story.

Overall, OFF was AMAZING. I hardly slept while I was there, since there was always something to do. And really, I can’t think of another event experience I’ve been involved in that has given me such an intense feeling of satisfaction. With tons of incredible improvisers and actors, a fantastically creative production team, devoted and detail-oriented management, and thoughtfully designed games and puzzles, I can’t wait until I get to do something like this again.

Dread and the Tragedy of the Commons

“Shaun of the Dead”

I once had a friend who, as an experiment, attempted to run a role-playing adventure that felt like a zombie-apocalypse-style horror movie. He set up a creepy soundtrack and gory movies in the background for ambiance. There was a fairly 3d representation of a house that we were trapped inside, and he had clever ideas about how to make the building fall apart over time. There were food and drinks and fun and everyone bought in to the theme…

But in the end, we called the game a failure. Horror stories are built around a growing scarcity of resources. People run out of easy solutions, like a too-convenient revolver, and are forced to survive with the worst kind of tools. Eventually, characters die as even human beings become a resource that continues to fail. D&D is not a game where resources disappear. A fighter remains just as strong whether they are fully healed or at death’s door. So there just isn’t enough tension!

Fortunately, there is a game designed to bring the tension and terror of these kind of stories to you and your gaming group. Dread, the world’s only Jenga-based roleplaying game.

The rules for Dread are simple. When you want to do something, pull a block from the tower and place it on top. If you knock over the tower, you fail and die in the worst way possible. If you knock the tower over on purpose? You die in the worst well possible, but you succeed at your final task! These simple rules allow for plenty of variations. Harder tasks may take two or even three pulls. I often add specific injuries that can require extra pulls in certain situations.

There is nothing like looking at a wobbly tower and knowing that you have to make a pull to move the story along. When death itself is on the line, what do you do? I hope you take this moment to reflect on one of the greatest Dilemmas of game theory.

The Tragedy of the Commons describes how groups of people tend to use up plentiful common goods without worrying about the consequences. Imagine a big group of friends in a room playing games together. Someone opens up a box of donut, but sets them in the neighboring room. Friends can walk into the room and eat a donut in private, but they are asked to only have two each to start. If there are more left, which seems likely, they can each have more.

I can admit it. I’m a donut eating monster. I’ll have my two, but I probably won’t ask if everyone has had two before grabbing a third. As long as I expect other people are taking care of themselves, I might even grab a fourth. So it shouldn’t be a surprise when my friend, purchaser of the aforementioned donuts, gets real mad that all the donuts are gone, declaring “I will never bring donuts again.”

The Tragedy of the Commons occurs whenever a group of people think about themselves as individuals rather than as a community. Communities are fair, attempting to find the greatest good for everyone. Individuals are looking for their own greatest good, and hoping that no Consequence steps in to shut things down. This is the problem of leaving your dishes in the sink and hoping someone else cleans them. This is the problem of bribery and pollution. It’s big.

The Tragedy of the Commons occurs whenever a group of people think about themselves as individuals rather than as a community. Communities are fair, attempting to find the greatest good for everyone. Individuals are looking for their own greatest good, and hoping that no Consequence steps in to shut things down. This is the problem of leaving your dishes in the sink and hoping someone else cleans them. This is the problem of bribery and pollution. It’s big.

In Dread, the Tragedy of the Commons shows up right away. As the story begins, players start pulling blocks for silly reasons. They want to check their email or search through someone’s room. The game is designed to be fun, so players act on that impulse! But eventually, their fun makes the tower wobbly. And now no one wants to act, because the consequence of continues action might be their character’s imminent demise. On the other hand, players may hold back from making pulls unless they are truly helpful to advancing the mission, leaving the tower stable and reducing the chances that all the characters die.

So how much fun should you have? Should you forsake fun for the sake of your group achieving it’s mission? I mean… I don’t know about you, but I’m all about maximum fun. And if that means I’m the class clown that gets taken out in Act One, well at least I’ll go out trying to see if I can water ski across a tightly packed zombie horde.

8 Stag Hunt and Timeline

Let’s talk about Risk! No, not the game. The feeling of going all in, hoping you’re going to hit it big. This episode starts with the example of Timeline, talks about the Stag Hunt dilemma, and finishes with a series of risk-filled recommendations.

The Crescendo-of-Doom Mechanic

A while back, designer Michael Iachini of Clay Crucible Games wrote an excellent post about what he called the Crescendo mechanic. According to Iachini, this occurs whenever “something a player could choose gets… more valuable the longer it goes unchosen.” Even though I had never thought about this as a mechanic before, I immediately knew exactly what he meant.

Crescendo means that a sub-par option becomes more favorable over time, due to increasing utility gains. While Iachini has plenty of examples in his post, my favorite has to be the Prospector role in Puerto Rico. Every turn, players take turns choosing one of the many roles in the game. Choosing the Prospector grants a single gold, which is almost never worthwhile when compared to what you could gain with other roles. However, each round, one extra gold piece is placed on any role not chosen, granting an incentive to grab those roles next time.

Crescendo means that a sub-par option becomes more favorable over time, due to increasing utility gains. While Iachini has plenty of examples in his post, my favorite has to be the Prospector role in Puerto Rico. Every turn, players take turns choosing one of the many roles in the game. Choosing the Prospector grants a single gold, which is almost never worthwhile when compared to what you could gain with other roles. However, each round, one extra gold piece is placed on any role not chosen, granting an incentive to grab those roles next time.

The bluffing game my friends and I played during Puerto Rico was all about seeing how long we could let money pile up on the Prospector before someone jumped on it. Two? Three? There are only so many rounds available in Puerto Rico before one player wins, and it hurts to squander a round on a sub-par choice. So this became a quick catch up mechanic, giving the player with the least efficient round the opportunity to jump in with a pile of cash.

But what about a sub-par option that gets worse over time? Cities and Knights of Catan features the Barbarian Horde. As the game progresses, players must use some of their resources to defend the land against the barbarians. If the land is defended, the player who defends the most gets a benefit. If the land is not successful in its defense, the player who defended the least gets punished. Spending resources to stay in the middle always feels like a waste, and it gets more and more tense as the barbarians get closer.

But what about a sub-par option that gets worse over time? Cities and Knights of Catan features the Barbarian Horde. As the game progresses, players must use some of their resources to defend the land against the barbarians. If the land is defended, the player who defends the most gets a benefit. If the land is not successful in its defense, the player who defended the least gets punished. Spending resources to stay in the middle always feels like a waste, and it gets more and more tense as the barbarians get closer.

Another great example is fighting against the siege engines in Shadows Over Camelot. Getting twelve on the board at once means instantly losing the game, but beating them doesn’t grant the player anything at all. Finishing other quests can give you a reward, but fighting the siege engines means you slowly lose cards and gain nothing for your efforts. Especially if the traitor of Camelot is in a mood to place catapults, this is simply a losing proposition. Instead of helping everyone win, your job is to slow down a coming defeat.

In each of these scenarios, there is a benefit to choosing the sub-par option. It just isn’t the best thing you could do. And between Crescendos and… whatever this is called, the biggest difference is that instead of waiting for a moment of great utility, you’re waiting for the moment when you will be most hurt if you don’t choose the sub-par option. Which means these are perfect examples of the Volunteer’s Dilemma in action—choosing to take a less beneficial outcome to benefit the rest of the group.

What am I supposed to call this? If I stick with the tempo theme, I could go with “Accelerando,” for gradually speeding up. Or “Symphony of Destruction?” Maybe “Falling into the Abyss?” Send me your thoughts on Twitter!

The Breadth of Betrayal

Board games with a traitor mechanic have been part of my games library for as long as I can remember. Strangely, when I ask people to define the mechanic, the answer tends to fall apart. Betrayal has a strong emotional component and many players identify any similar emotion as a kind of betrayal. Did someone attack you when you weren’t ready for it? Traitor! Did they break an alliance you’d thought was secure? Betrayal!

Board games with a traitor mechanic have been part of my games library for as long as I can remember. Strangely, when I ask people to define the mechanic, the answer tends to fall apart. Betrayal has a strong emotional component and many players identify any similar emotion as a kind of betrayal. Did someone attack you when you weren’t ready for it? Traitor! Did they break an alliance you’d thought was secure? Betrayal!

Even among games that have a defined traitor, it turns out that there is a fairly wide array of mechanics that make that betrayal real. Since this is a topic I hold near and dear to my heart, I thought I’d take a moment to work through some of these mechanics. Here’s a quick classification.

Games Where Someone Can Lie to You

Being lied to is never fun, especially when you know that your friend lied right to your face to gain an advantage over you. In Coup, lying is a defense mechanism. If someone knows what role cards you actually have, they are better able to tear you apart. Lying about what roles you have keeps the game on unsteady ground, and plenty of those lies will never be discovered, because they aren’t recorded from turn to turn. Other games that fit this mold are Secret Hitler, Resistance, and Avalon.

On the other hand, Sheriff of Nottingham is a game all about lying to someone, then immediately gloating over your web of half-truths. Each round, one of you takes the role of the Sheriff, while everyone else tries to get goods through to market. You put a number of resource cards into your bag, then declare what you have. But the game makes it difficult to be perfectly truthful and perfectly efficient at the same time. You can only declare one type of resource, along with the number of those you have in your bag. You can put a maximum of five cards in the bag. So what if you have three apples and want to add a coin? You have to lie and call it four apples. Or leave the coin at home and get fewer points than possible. Worse, there are contraband cards which are never legal. So, can you lie and bribe the Sheriff to avoid searching your goods? What happens when the Sheriff realizes they’ve been tricked?

Games Where Someone Can Hurt You

The emotional feeling of being betrayed is not a pleasant one. You and a friend are playing a competitive game, but seem to have a strong alliance. At a climactic moment, when you expect them to support you, they stab you right in the back. We use the word “stab” in this metaphor for a reason. There are plenty of games like this. In Diplomacy, alliances are meant to shift over time, and those shifts always leave someone broken and bruised. Sometimes, they can even leave friendships broken and bruised. But this can also happen in games like Risk or Catan. This kind of betrayal hurts even more because it isn’t a mechanic in the game, it’s a choice.

Every single competitive game with player elimination fits this category. As long as I can work to kick you out of the game, there is the possibility that I can lie about my intentions and then stab you in the back. In fact, it makes it easier for me to win. I’d rather fight an unprepared opponent than one who has their defenses pointed right at me.

Games Where You Are Trying to Find the Traitor

In games like Werewolf, the entire premise revolves around discovering the hidden traitors. There aren’t any other goals. When you find the werewolves, you win. If you fail, you lose. These games force players to lie constantly, and players who are poor liars are at an extreme disadvantage. Fans of these games often love them because they have an abnormal opportunity to lie to their friends, or because they get to be the hero who can always ferret out the truth.

Games like BANG! switch this up by granting players other things to do besides lie. You also have to shoot guns at the other players. In BANG!, players need to figure out the roles of the other players and attempt to remove them from the game in a specific order. Players often find themselves hurting their secret allies to keep their roles hidden from the Sheriff and Deputies.

Games like BANG! switch this up by granting players other things to do besides lie. You also have to shoot guns at the other players. In BANG!, players need to figure out the roles of the other players and attempt to remove them from the game in a specific order. Players often find themselves hurting their secret allies to keep their roles hidden from the Sheriff and Deputies.

Games Where You Are Trying to Win and the Traitor is Trying to Stop You the Whole Time

For me, these games are the peak of Mount Betrayal. Players have an active goal of winning the game, while one player is attempting to secretly stop that from happening. In Shadows Over Camelot, the traitor often makes suboptimal choices in attempt to appear like an unlucky player. Midway through the game, players may begin accusing their peers of being a traitor. Correct guesses help with victory, while incorrect ones bring the knights closer to defeat. Of course, once the traitor has been revealed, all gloves are off. The traitor can spend the rest of the game being as malicious as possible.

In Battlestar Galactica, the Exodus Expansion adds a pile of offensive capabilities to Cylons once they’ve been revealed. Human players might almost regret revealing the traitors as Cylons are able to throw tons of troops and force major crises in their quest to destroy humanity.

These games allow a traitor to lie for a short period of time, but the game doesn’t end when someone catches them. This is an especially good option for terrible liars who just want their chance to play the villain.

Games Where Someone Becomes a Traitor

Now these games are interesting. These games toy with the fact that you are a team, letting you believe you are one of the heroes, and then crushes your dreams all in an instant. You may have been the leader of the heroic resistance, with all the tools of light at your disposal, and suddenly you are the villain. Sometimes, everyone knows it. Other times, they never see betrayal coming. Halfway through a game of Battlestar Galactica, players get a second round of loyalty cards, which makes it very likely that someone who once thought they were human suddenly become a Cylon.

Mansions of Madness has an incredible sanity mechanic that I’ve never seen before. When your character loses their sanity, they aren’t removed from the game. Rather, you gain an Insanity card. Some of these cards have alternate win conditions. Some of them don’t. And you aren’t allowed to tell anyone else what’s on your card. Which means it is absolutely possible that you are still 100% on the side of good, but no one can trust you anymore. It also means that maybe you just want to watch the world burn instead of fighting the big bad in the square next to you.

And of course, there’s one of my favorite games of all time, Betrayal at House on the Hill. Everyone who plays Betrayal knows that the Haunt phase is coming, where one of the players will suddenly become the villain with some nefarious scheme. But no one knows when the Haunt will occur, who the betrayer will be, or what the evil scheme will be. Which means that while the early game is cooperative, very few people cooperate! It’s an exploration game where you want to hide from your companions. You want to be alone and get the Dynamite. You take joy when the other players get hurt in a trap, because it means that either they’ll be a weaker villain when you have to fight them, or that you’ll be the strongest player around when it’s time to Betray. It’s a beautiful game and the betrayal mechanic is entirely random, and therefore, entirely fair.

And of course, there’s one of my favorite games of all time, Betrayal at House on the Hill. Everyone who plays Betrayal knows that the Haunt phase is coming, where one of the players will suddenly become the villain with some nefarious scheme. But no one knows when the Haunt will occur, who the betrayer will be, or what the evil scheme will be. Which means that while the early game is cooperative, very few people cooperate! It’s an exploration game where you want to hide from your companions. You want to be alone and get the Dynamite. You take joy when the other players get hurt in a trap, because it means that either they’ll be a weaker villain when you have to fight them, or that you’ll be the strongest player around when it’s time to Betray. It’s a beautiful game and the betrayal mechanic is entirely random, and therefore, entirely fair.

I love games about betrayal. There are so many varieties and I find them all so much more interesting and elegant than simply attacking a friend in a wargame like Risk. Sure, I enjoy cooperation. But infinitely better is the idea of beating all of your opponents while they’re trying to bring you down. Being the traitor is thrilling and I highly recommend it, like I recommend every single one of these games.