Last week was the culmination of mountains of research and development as my team and I launched the Emoticode, a three-day livestream on Twitch promoting the release of Activision’s Call of Duty: WWII. Over the course of those three days and eight hundred-thousand views, thousands of players competed to crack a series of forty-five ciphers, with solvers gaining a beta invite to the game. In the end, my devious ciphers stood up to the onslaught for almost fifty hours, and they would indeed have been doomed without me watching for the perfect moment to drop just the right hints.

Last week was the culmination of mountains of research and development as my team and I launched the Emoticode, a three-day livestream on Twitch promoting the release of Activision’s Call of Duty: WWII. Over the course of those three days and eight hundred-thousand views, thousands of players competed to crack a series of forty-five ciphers, with solvers gaining a beta invite to the game. In the end, my devious ciphers stood up to the onslaught for almost fifty hours, and they would indeed have been doomed without me watching for the perfect moment to drop just the right hints.

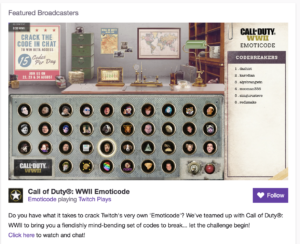

At a baseline, each of the ciphers had to stand up to random brute-force attacks by hundreds of guessers for at least an hour. Meanwhile, they still needed to be solvable by fans who had potentially never cracked a cipher in their lives. Best of all, the cipher would be transmitted only by a series of blinking emotes in the Emoticode typewriter with no direction or guidance unless a hint was needed. A wide web of impenetrable difficulty until a solver can find the single, clever way to break through.

This is the kind of challenge I enjoy the most.

It turned out that the solution to this challenge was scaffolding. You probably remember this from your math classes—you studied addition, then learned that multiplication was just like adding, but faster! Your skills leveled up over time. When we build a proper scaffold, we allow players to build their skills. Which is why you should play Lords of Waterdeep before you take a crack at Agricola. But back to codes…

Our first ciphers were the simplest. Starting from a few hints, players needed to translate the Emotes into letters and numbers. In this alphabet, you might get emotes that translate to ?A??IN? and have to come up with the right solution. Since you know most of the letters, those ?s would have to be C, G, K, P, or Q. G is a good guess for the last letter, and soon we’re at !solve PACKING and victory. Of course, it wasn’t quite that easy, and it instantly got harder.

Our first ciphers were the simplest. Starting from a few hints, players needed to translate the Emotes into letters and numbers. In this alphabet, you might get emotes that translate to ?A??IN? and have to come up with the right solution. Since you know most of the letters, those ?s would have to be C, G, K, P, or Q. G is a good guess for the last letter, and soon we’re at !solve PACKING and victory. Of course, it wasn’t quite that easy, and it instantly got harder.

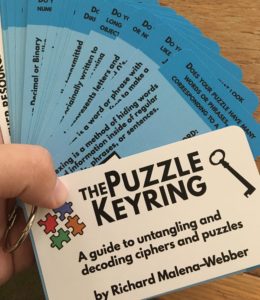

Before too long, we moved into simple substitution, like the Caesar or Atbash ciphers. Not much harder, but then we’d do some transposition, like a Rail Fence or Columnar Substitution. And then? We’d start doing both at the same time. I’d throw in Braille or Morse Code to keep things fresh, and then dig into some Binary or Hexadecimal digits. By the end of the Emoticode, our top solvers knew every single one of these types of ciphering systems, plus Vigenere, Playfair, and One-Time Pads. It was incredible to see these brand new solvers have a series of tricks they could bring out to try against my ciphers! On the other hand, if I’d started with a Rail Fence Hexadecimal Atbash puzzle, absolutely none of this would have ever occurred.

Scaffolding is something I learned as a teacher, but you often see it in board games as well. The extremely new Apocrypha has a pre-wrapped deck that you are meant to play without shuffling at all! A video guide helps lead you through the scenario. Once you play those early missions, additional rules and features can be tacked on to make things difficult in fun ways, not just through complexity and obfuscation. One of my favorite games in the world, Race for the Galaxy, fails to do this, and I have the worst time convincing new players to take a chance on the game.

By the end of the Emoticode experience, I’d written forty-five ciphers and spent almost that many hours moderating Twitch and Discord servers filled with people trying to solve my devious codes. A group of solvers banded together and are now looking for more puzzles and codes to solve as a new team! For a guy who teaches Cryptography, this was the perfect outcome. Along with my immediate twenty straight hours of sleep.

(And no, this was not a trial to get into the NSA. As I kept getting asked on Twitch every ten minutes.)

Folks, I was so good for so long. I didn’t buy Overwatch because I know myself. As soon as I picked it up, I knew I’d dive in and battle my way up into the competitive levels. I can’t help it—I don’t want to help it! I love playing FPS games, and once I get started the only thing that gets me to stop is the eternal knowledge that rent is coming due.

Folks, I was so good for so long. I didn’t buy Overwatch because I know myself. As soon as I picked it up, I knew I’d dive in and battle my way up into the competitive levels. I can’t help it—I don’t want to help it! I love playing FPS games, and once I get started the only thing that gets me to stop is the eternal knowledge that rent is coming due.

What happens next? The stronger team immediately becomes weaker but they don’t yet know how. Overwatch is a game about team balance, so suddenly losing a healer or a tank can severely change things. Even losing a major damage dealer allows the other team a huge opportunity. While the strong team is trying to figure things out and possibly take down one of their former teammates, the trapped team has a new chance to break out and make the game a little bit more fair.

What happens next? The stronger team immediately becomes weaker but they don’t yet know how. Overwatch is a game about team balance, so suddenly losing a healer or a tank can severely change things. Even losing a major damage dealer allows the other team a huge opportunity. While the strong team is trying to figure things out and possibly take down one of their former teammates, the trapped team has a new chance to break out and make the game a little bit more fair. The early version wasn’t fantastic, I admit. I’d decided to make this educational and try to teach people how to solve puzzles. After years of playing, running, and making puzzles, I knew this was a difficult task. It’s like learning proofs in Geometry—there’s a moment where it clicks, but all the moments before that can be filled with frustration.

The early version wasn’t fantastic, I admit. I’d decided to make this educational and try to teach people how to solve puzzles. After years of playing, running, and making puzzles, I knew this was a difficult task. It’s like learning proofs in Geometry—there’s a moment where it clicks, but all the moments before that can be filled with frustration. As a teacher, I don’t often have the experience of making things like this. I know plenty of game designers and developers who build prototypes and musicians who make and produce their own albums and merchandise, but I haven’t been that kind of person. Let me tell you, it feels pretty fantastic.

As a teacher, I don’t often have the experience of making things like this. I know plenty of game designers and developers who build prototypes and musicians who make and produce their own albums and merchandise, but I haven’t been that kind of person. Let me tell you, it feels pretty fantastic. I posted a picture on Twitter last week about my curriculum for my last Games and Game Theory class. I guess folks were surprised that it was really just a big stack of games? I’m sure that I have a syllabus somewhere but, like my students, I probably recycled it as soon as the first class was over. The whole point of the class is to find out how game theory shows up in the board games we all know and love, and these games exemplify some of those important problems. Today I want to talk about two of them in particular and how they relate to the terrible study of probability.

I posted a picture on Twitter last week about my curriculum for my last Games and Game Theory class. I guess folks were surprised that it was really just a big stack of games? I’m sure that I have a syllabus somewhere but, like my students, I probably recycled it as soon as the first class was over. The whole point of the class is to find out how game theory shows up in the board games we all know and love, and these games exemplify some of those important problems. Today I want to talk about two of them in particular and how they relate to the terrible study of probability.

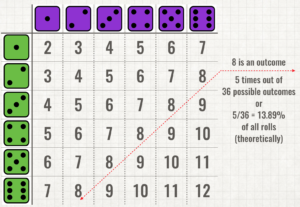

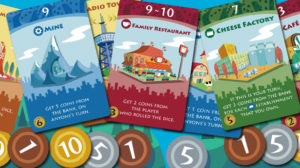

In Machi Koro, you are trying to build a city filled with businesses and attractions. On your turn, you roll and collect gold for every business you have showing the same number at the top. As you progress through the game, you have the option of rolling one or two dice. The businesses that trigger on 7 through 12 may be a little more glamorous, but those low numbers can keep you chugging along through the game for quite some time. At some point, every player has to make the switch, and the game suddenly changes dramatically. Machi Koro also has restaurants, which allow you to steal gold from players when certain numbers come up, and that makes this game feel pretty mean and hopeless sometimes. In the end, players need to use probability, luck, and an efficient engine to build their attractions before anyone else.

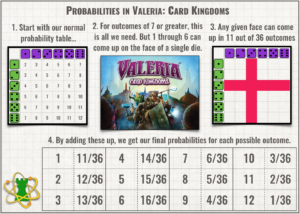

In Machi Koro, you are trying to build a city filled with businesses and attractions. On your turn, you roll and collect gold for every business you have showing the same number at the top. As you progress through the game, you have the option of rolling one or two dice. The businesses that trigger on 7 through 12 may be a little more glamorous, but those low numbers can keep you chugging along through the game for quite some time. At some point, every player has to make the switch, and the game suddenly changes dramatically. Machi Koro also has restaurants, which allow you to steal gold from players when certain numbers come up, and that makes this game feel pretty mean and hopeless sometimes. In the end, players need to use probability, luck, and an efficient engine to build their attractions before anyone else. While similar in style, Valeria: Card Kingdoms has some great tweaks that makes it a very fun and engaging game. With very little inter-player conflict, everyone is free to hoard resources all they want, and they come quickly! Every card has a benefit you gain either when you roll its number, or when another player rolls it on their turn. Valeria ramps up like no game I’ve ever seen. While early turns may net you just a single gold, by the end of the game, one lucky roll of the dice can easily net you twenty or more currency. With multiple paths to victory, players are free to choose exactly what kind of citizens they want in their city, monsters they want to destroy, and domains to add to their kingdoms. This game is always a contender at my game nights!

While similar in style, Valeria: Card Kingdoms has some great tweaks that makes it a very fun and engaging game. With very little inter-player conflict, everyone is free to hoard resources all they want, and they come quickly! Every card has a benefit you gain either when you roll its number, or when another player rolls it on their turn. Valeria ramps up like no game I’ve ever seen. While early turns may net you just a single gold, by the end of the game, one lucky roll of the dice can easily net you twenty or more currency. With multiple paths to victory, players are free to choose exactly what kind of citizens they want in their city, monsters they want to destroy, and domains to add to their kingdoms. This game is always a contender at my game nights!

At

At

In January 2017, three professional poker players were challenged to play against

In January 2017, three professional poker players were challenged to play against