Xanathar is basically designed to give monologues to his goldfish every single day.

In a recent Unearthed Arcana post, Dungeons and Dragons Creative Lead Mike Mearls talked about what he describes as the “three-pillar experience.” The overall design behind D&D is that the game is supported by three major activities: combat, social interaction, and exploration. Unfortunately, combat is the easiest to define in terms of actions and rewards. Since 3rd Edition, player experience points has come almost entirely from these combat encounters. Nods have always been made towards story rewards, but never in as clear a way as the amount of experience points gained per destroyed skeleton and zombie. In a very simple game theoretic way, if rewards only come from combat, then doing anything else is a waste of time.

Mearls has provided a plan in his post to overhaul the entire experience system to one based on milestones representing each pillar. While there is a lot of elegance to this approach, I think it serves to simplify things rather than to make everything equally robust. Which is why I decided to come up with a solution of my own.

The Monologue Mechanic is my approach to bolstering the social interaction pillar of gameplay in a narrative way. I introduce a series of NPCs called critics, who only exist to learn about the players and their journeys. They want to hear the stories of each adventure and turn them into legends! Or potentially make fun of the heroes, which is why I used Statler and Waldorf as my major examples.

One method to creating legends is to build real villainous monologues. When a hero gets a chance to listen to a diabolical rant, they suddenly have plenty of new opportunities to build a story. One hero might furiously scribble down the entire evil plan, making sure to get every nuance about both the future and the past. This hero wants to tear down the villain’s entire engine, just like most of the crime dramas I’ve ever seen. On the other hand, some heroes want the chance to engage with the villain and build up a dialogue before the climactic encounter. When face-to-face with the lich mastermind, a hero might want to drop in a few clever one-liners!

As a reward for their actions, heroes gain everlasting renown across the land. While a hero can grow a good deal of fame by helping a community, things grow exponentially when someone is out there telling a real legend. A famous hero can change the world in wildly different ways than one who acts in secret. A robust Fame System can also give characters rewards in terms of recognition and even the kind of Fans who would be willing to put it all on the line to help their favorite champion of the land.

My hope is that by creating The Monologue Mechanic, players will be more excited to engage in their own heroic story. Of course, other game systems exist that put the focus on different pillars than D&D. Fiasco is all about improvising and building a complete story from some cleverly linked details, and while combat is possible, it’s all just another step in the wild and sometimes heavy narration. Numenera leaps into exploration by giving players a vast unknown world that is tied to our own in only the most ephemeral ways, then providing a settlement to build up in the face of that mystery.

My hope is that by creating The Monologue Mechanic, players will be more excited to engage in their own heroic story. Of course, other game systems exist that put the focus on different pillars than D&D. Fiasco is all about improvising and building a complete story from some cleverly linked details, and while combat is possible, it’s all just another step in the wild and sometimes heavy narration. Numenera leaps into exploration by giving players a vast unknown world that is tied to our own in only the most ephemeral ways, then providing a settlement to build up in the face of that mystery.

I think role-playing is at its best when tied to a strong group of story-driven players. If that sounds like something you might be in for, feel free to check out The Monologue Mechanic on DMs Guild now!

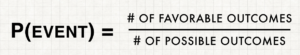

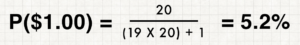

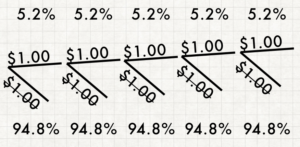

Let’s start with Wilbert. Determining the probability of an event occurring requires us to create a pretty simple ratio. On bottom of the fraction are the number of possible outcomes in a situation. On top, the number of favorable outcomes. In this case, we want to find out the number of possible spins of the wheel and the number of ways to get $1.00.

Let’s start with Wilbert. Determining the probability of an event occurring requires us to create a pretty simple ratio. On bottom of the fraction are the number of possible outcomes in a situation. On top, the number of favorable outcomes. In this case, we want to find out the number of possible spins of the wheel and the number of ways to get $1.00.

When it comes down to it, the right answer is to build a probability tree. When we do this, we can start to put together the actual solution. In probability terms, this is a then question, as in event A occurs, then event B occurs. In then problems, we multiply the probabilities of each outcome together. Which means the odds of these five $1.00 spins happening in a row is roughly one in two and a half million.

When it comes down to it, the right answer is to build a probability tree. When we do this, we can start to put together the actual solution. In probability terms, this is a then question, as in event A occurs, then event B occurs. In then problems, we multiply the probabilities of each outcome together. Which means the odds of these five $1.00 spins happening in a row is roughly one in two and a half million. As I wrap up final production on the

As I wrap up final production on the

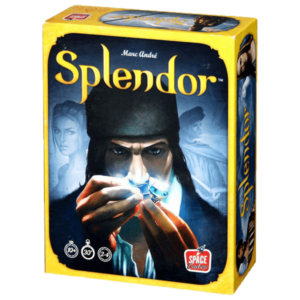

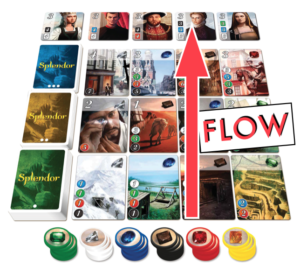

Have you played Splendor? If not, you really should. It’s a great game where you play a gem merchant, collecting gem resources to buy better and better mines and shops to sell your wares. Purchasing these mines and shops give you permanent gem resources, allowing you to buy better mines and shops and so on. The game is fantastic because of the huge ramp that becomes available to you during play. At the start, you strive for the most basic mines. By the end, you could buy those on a whim, but you’re on the lookout for better and better storefronts. The game ends when someone hits fifteen victory points, so its important for players to build a gem engine, gathering points as quickly as possible. When you do? It’s a very satisfying experience.

Have you played Splendor? If not, you really should. It’s a great game where you play a gem merchant, collecting gem resources to buy better and better mines and shops to sell your wares. Purchasing these mines and shops give you permanent gem resources, allowing you to buy better mines and shops and so on. The game is fantastic because of the huge ramp that becomes available to you during play. At the start, you strive for the most basic mines. By the end, you could buy those on a whim, but you’re on the lookout for better and better storefronts. The game ends when someone hits fifteen victory points, so its important for players to build a gem engine, gathering points as quickly as possible. When you do? It’s a very satisfying experience. One day, I decided to play in a Splendor tournament in Portland. As I recall, the winner would earn some promo goods, but I admit that I lost focus on the prize very quickly. This was the day I learned about the Splendor problem.

One day, I decided to play in a Splendor tournament in Portland. As I recall, the winner would earn some promo goods, but I admit that I lost focus on the prize very quickly. This was the day I learned about the Splendor problem. The new expansion Cities of Splendor adds four variants to the game. Instead of Lords at the top, there are Cities. These either require a TON of gem cards to get, or a massive pile of victory points. Plus, now the game doesn’t exactly end at a victory point total. The game ends on the round when someone gets a City, and only players with a City are in the running to win the game.

The new expansion Cities of Splendor adds four variants to the game. Instead of Lords at the top, there are Cities. These either require a TON of gem cards to get, or a massive pile of victory points. Plus, now the game doesn’t exactly end at a victory point total. The game ends on the round when someone gets a City, and only players with a City are in the running to win the game.